(In)Coherence

(In)Coherence

Mary Shelley Started It

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

In this episode we contend with monstrosity as we look into creativity’s double binds: The unintended consequences of scientific creation.

What it means to be human in the presence of moral challenges and the absence of certainty. How science fiction may show that paranoia is precedented when it comes to evaluating our rush toward artificial intelligence.

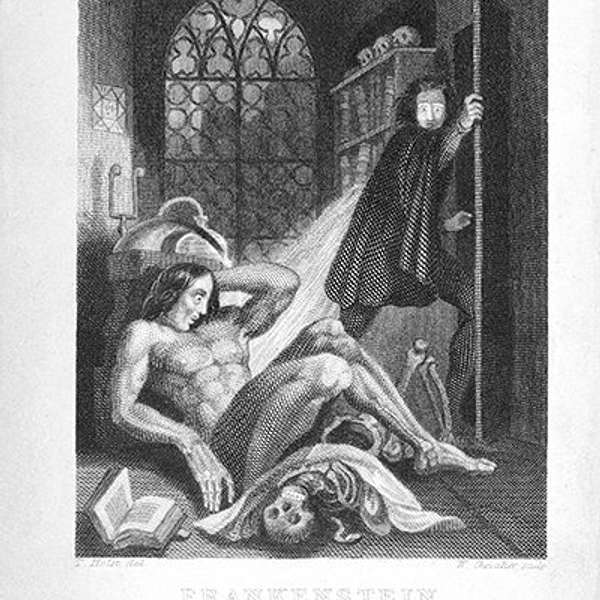

Mary Shelley started it all. Frankenstein was published in 1818.

Mary Shelley had spent the year without a summer at Lake Geneva in 1816. The gloomy weather found her writing by candlelight about Victor Frankenstein, a scientist and inventor who finds the secret to creating artificial life, and creating a conscious life.

The monster creation became the subject of dozens of movies. (The 1931 James Whale version starring Boris Karloff as the Monster was made with a $262,000 budget. Young Frankenstein by Mel Brooks may be the second-best known.)

In part one, Larry Lockridge, professor emeritus at New York University, talks about virtue ethics and botched creations. Owen Flanagan, neurobiologist and professor of philosophy at Duke University, discusses his founding of a new term in philosophy, neuro existentialism--and how motivated are we, actually, to flourish? Science fiction illustrator Vincent Di Fate talks about why the brain itself, "a rather homely organ," has played such a starring role in sci-fi imagery.

Producer and Host: Ellen Berkovitch

Co-Producer and Interviewer this episode: Mary Jo Vath

Guests: Larry Lockridge, Owen Flanagan, Vincent Di Fate

VoiceOver Artist: Roberto Sharpe

Post-Production and Theme Music: Dennis Javier Jasso

Creative Commons Samples: Spinning Merkaba, The Stars Look Different under a creative commons license courtesy ccmixter.org

STEAMPlant Team: Ellen Berkovitch, Mary Jo Vath, Iliyan Ivanov, Agnes Mocsy

Funding: STEAMPlant grant from Pratt Institute.

Ellen Berkovitch: As we work on our podcast (in)Coherence, we’re determined to host provocative conversations about the possible intersections of neuroscience and the arts. I’m Ellen Berkovitch and I’m the host and producer of InCoherence. Our show is funded by a Steamplant grant from Pratt Institute.

We talked last time with a neuroscientist, Joseph Ledoux from NYU, about what neuroscience has learned about the human experience of danger and the human emotion of fear. This time on Inc we look into art.

[Theme music]

Mary Jo Vath: I’m Mary Jo Vath. I’m a painter and I teach painting and art history at the School of Visual Arts in NY. I’m the artist on the team and together with Ellen, we represent the humanities part of this project.

EB: My colleague and friend Mary Jo Vath was the first person to really suggest that our project attempt to turn the tables and find the artists, asking the neuroscientists questions. We’re going to acknowledge that was a bit of a terrifying proposition.

MJV: I didn’t know what part I was going to play in the research, but I began digging and one thing led to another and I became fascinated with the art of science fiction, and its portrayals of the brain, brain science, and brain scientists. How I ended up looking at Frankenstein was just an intuition while I was researching sci-fi, bc it had been cited v very often as the first science fiction.

EB: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is in fact a literary marvel.

MJV: And I had not read it in years.. And so a lot of the received notions we have about what’s in the book aren’t really there.

EB: She wrote it when she was 18. It was first published in 1818. It had a second edition in 1831.

MJV: In the book there’s nothing about a brain while in the movie they use a criminal’s brain for the monster which is supposed to explain the monster’s behavior.

EB: The monster has become popularly known as Frankenstein but we’ll make the distinction that Victor Frankenstein was not the name of the monster but the name of the scientist who created the monster. The monster has no name.

Let’s begin.

Voice actor Roberto Sharpe: It was on a dreary night of November that I beheld the accomplishment of my toils..

.. How can I describe my emotions at this catastrophe?

EB: As Mary Jo and I were looking at the Edison silent film on YouTube, we were giggling about saucepans and cauldrons, because I had become fixated on the fact that what was being whipped up, like with a whisk, was happening in a saucepan

MJV (laughing) Well it was a cauldron.. and it’s very alchemical.

You know there’s a scene shot where the monster.

He ( scientist Victor Frankenstein) has his girlfriend there and she goes in the other room. But we see most of the action in the mirror.. In a number of instances, Frankenstein—Victor Frankenstein—is in one spot and the monster is in the mirror. And in fact at the end, he disappears in the mirror. The monster.. and all Frankenstein sees is himself

Voice actor RS: When I found so astonishing a power placed within my hands I hesitated a long time concerning the manner in which I should employ it. (etc.)

MJ: You have several layers of convention around this monster. And he in the book is articulate and initially quite benevolent and by the time you get to Boris Karloff’s Frankenstein, he’s practically unable to speak, he’s such a brute.

EB: These core ethical questions about the morality of scientific experiment, of unintended consequences, are things we’re really interested in as we engage in this exploration of neuroscience and art.

Voice actor RS: I doubted.. etc.

MJV: To examine the ethics in the novel, I talked with Larry Lockridge professor emeritus of English at NYU.

Larry Lockridge: I have written on Frankenstein, I have taught Frankenstein

[Fx: Frankenstein trailer]

MJV: A lot of the popular conceptions about the book actually stem from the movies. there’s a lot of things that don’t happen in the book, like a lot!

LL: For example, Mary Shelley does not convey exactly how Frankenstein went about galvanizing or bringing to life and putting together his monster.

And yet of course that is dwelt on very much in cinema.

MJ And also there is a scene where they get a criminal brain to use for the monster which is not in the book at all.

I want to ask you if in some ways this book isn’t more about ethics than about science…

LL: Certainly on every page ethics is implicated one way or another, the science is not directly addressed as science.

The Monster has a great deal of what we call virtue ethics, he says when he came into being he was virtuous, he glowed with benevolence.

EB: A mere mortal moment here to flesh out this question of what is virtue ethics?

LL: Virtue ethics is a theory that was between consequentialist theory such as we see in Bentham—an act is good to to the extent it produces favorable consequences, on the one hand—and then the Kantian notion that virtue is its own reward; there’s an intrinsic rightness or wrongness to any act. So instead of consequences you judge the quality of the act.

Virtue ethics takes an in-between position, which goes back to Aristotle. It de-emphasizes the notion of action. We have predispositions we call virtue that lead us to good or to bad. If you have virtuous character, consequences will more or less take care of themselves.

But Mary Shelley comes along and sort of blasts that out of the water and says you can have all sorts of virtuous predisposition, look at Frankenstein's monster. He becomes a serial killer.

{chuckles}

MJ: Well he’s enraged with Frankenstein because Frankenstein rejects him, so he punishes Frankenstein not by killing Frankenstein, but by killing everyone he loves because the monster is unloved by everyone.

[Fx movie preview, with screams]

MJ: I’ve seen the novel characterized as the only creation myth that matters now. I asked Larry Lockridge about that.

LL: I’m not sure that any creation myth has this dark prophecy.

EB: Dark prophecy was literally in the skies when Mary Shelley was writing Frankenstein. She was at Lake Geneva. The year was 1816.

She wasn’t Mary Shelley yet, her name was Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin but Mary Godwin had gone with Percy Shelley and Lord Byron on summer holiday at Lake Geneva. 1816 came to be called the year without a summer because the skies never lightened. There were freezing storms of volcanic ash from the eruption of Mt. Tambura in Indonesia the previous year.

LL: Mary Godwin’s presentation of the monster coming into sentient awareness is strictly Humean-Lockean. We see him in that chapter where he’s narrating to Frankenstein his own origin, his memory of that his coming into being and it’s all the senses impinging on him..

MJV: What Mary Shelley describes through the monster is synaesthesia.

Voiceover actor RS: All the events of that period...

MJ: When I think that Mary Shelley was barely 18 the questions are profound and that’s why it’s still with us and that’s why it’s become this screen that can be projected on. One of my main questions is: How did she know?

LL: There’s one thing I wanted to point out having to do with the creation myth.

And that’s a very strong analogy between one of William Blake's prophetic book and Frankenstein.

Its the book of Urizen, that’s spelled U R I Z E N .

There is a creation myth and it’s the visionary power Los or imagination with his hammer creating the human form out of his mighty opposite, Urizen.

And He tries to fashion the human form out of his mighty opposite, Urizen. He tries to fashion the human form, but he botches it, he terribly botches it, and instead of the beautiful human form which Blake worshiped, he creates a mess. A stagnant, repulsive mess and he’s disgusted by his own work and backs away.

MJV: When we look back at the novel, we tend to only remember two characters, Frankenstein and his maxi-me, the monster. We overlook the character of the scientist's best friend, Henri Clerval.

LL: There’s a very serious division of labor between Clerval and Frankenstein. Frankenstein is interested in natural philosophy and science and wants to understand the causes of things. And Clerval concerns himself with the moral relation of things.

Now this divorce of science from ethics is I think implicit in everything that follows in the novel, and Mary Shelley sees that as a fateful and a terrible false dichotomy.

[theme music-intro to Part 2]

EB: When we shared this episode with our colleague Iliyan Ivanov , he suggested that Victor Frankenstein had solved the two paramount mysteries: the creation of life and the creation of conscious life. His drive to do that also drove him to a new set of moral norms that he had established for himself, raising the question: Do ingenuity and creativity give the creator license to disrupt moral norms?

The creation scientist Victor Frankenstein has been compared to the 20th-century physicist and father so-called, of the atomic bomb Robert Oppenheimer. Underscoring the darkest side of scientific invention:

Voice of Robert Oppenheimer: I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, t he Bhagavad Gita. Visnu is trying to persuade the prince that he should do his duty and to impress, takes on multi-armed form and says, "Now I am become death. The destroyer of worlds."

{Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lb13ynu3Ia}

Part 2: Owen Flanagan Interview

EB:

As we continued to visualize other guests who we might invite to this show, to talk about values and virtue and neuroscience we alighted fortunately on a Duke University neurobiologist and philosopher.

Owen Flanagan: Yeah. Sometimes you need a word to describe something so maybe 15 years ago I came up with this word neuro-existentialism.

OF: So I’m Owen Flanagan, I’m a professor of philosophy at Duke University

Existentialism as philosophers use it describes a certain movement in philosophy and I describe three different periods of existentialism you know, and you hear these names in philosophy.

Soren Kierkegaard, great Danish pre existentialist, Friedrich Nietzsche and Fyodor Dostoevesky. One reason they’re usually classed as existentialist philosophers is they start to worry about the question of whether there’s a god to secure the meaning and significance of a life.

Two out of three of them, Soren Kierkegaard and Fyodor Dostoevsky, are theists, they're powerful believers in a god, Nietzsche is not of course. Nietzsche is the one who announced god is dead. But they’re all worried about the same thing. They see Europeans are becoming more and more secular — and they’re worried if people become more and more secular, then they’ll lose a sense of meaning , purpose and significance.

EB: It should also be said that the genocides of World War II and the Holocaust kickstarted scientific progress into more and more efficient killing machines.

OF: The second existentialism is caused by things like the Holocaust. How is it possible that decent human beings, most of whom were Christian, ended up perpetuating this great tragedy and loss of faith in humans?

So what I describe as neuro-existentialism is kind of a anxiety caused by people starting to realize that explanations are starting to be given for what it means to be a human in scientific terms.

Why does that cause anxiety?

Well, Because a traditional, more humanistic image of us, thinks of us as made in God’s image. Having free will and agency — creating a moral life, being responsible for our actions, and the more and more human sciences start to give explanations for our behavior in something like causal terms or mechanistic terms there is a loss of a sense of self or soul.

EB: I told Owen we had been looking into Frankenstein as an example of this hybrid construction, the entity the MONSTER— and as Mary Jo said,

MJV: The monster is unloved by everyone.

EB: Ok, that’s pretty heavy

EB to OF- When you come to moral psychology how do we deal with some of these ethical problems—what is created is not always good?

OF: so one of the things you’re bringing up in bringing in Frankenstein is there’s not just neuroscience out there that is trying to get beneath the surface and figure out what’s going on either in the machine or the ghost in the machine. But you mentioned evolutionary psychology.. Or biological theories of evolution.. where we’d trace back origins of various conceptions of what’s good or what's bad. How selfish we are or not or not selfish.

What our sense of beauty is, or not, and where it came from and how it evolved.

There’s that, there are evolutionary explanations, which after all are relatively recent when you think about it.

Darwin’s Origin of the Species is I believe 1848, so we’re not even 200 years after Darwin.

Neuroscience, we only started staining neurons in about 1903-4. Ramon y Cajal in Spain--and then of course there’s AI .

So all these things come together and affect the self-image of humans. As far as the ethical issues, it is my personal view that neuroscience is overrated but not necessarily by neuroscientists.

Now in the case of ethics there’s been a lot of work of people using brain images on what are called trolley problems.

[Fx: Trolley Problems]

OF: So, there’s a train it’s loose, it’s heading toward five adorable children, but you happen to be standing at the switch so you can switch it so it doesn’t hit the five adorable children but hits a middle-aged person on the other track.

The question is what should you do in that situation, and what would you do?

People look at the brain and find out what areas are active, and in that case 90% of Americans choose to switch it or think you ought to switch it. Then there are other cases just like it logically but are different.

The loose train is going toward five adorable children but instead of there being a track you can switch it to, you happen to be standing on a footbridge above it, and there’s a middle-aged person leaning over and somehow or other, you’re smart enough to realize if you just nudge that person onto the tracks they’ll stop the train.

They’re equivalent in the sense that either case you kill a person but in the second case 90% of Americans say you shouldn’t and different parts of the brain light up in that situation.

Without going into that, what does that show? It doesn’t show what the right thing to do is. It doesn’t show why people make the decision what the social reasons are behind it. It just tells you what part of the brain lights up when people do that sort of thing.

EB: Something really important to Owen Flanagan’s work is his thinking about the concept of flourishing in the context of ethics and human lives.

EB: Your interest in flourishing and eudaimonics is fundamentally a sort of --I don’t know what neuroscience would call it, whether it would call it higher-order theory, It raises a question whether flourishing is a biological imperative or a social ideal or do those things have to be distinct from one another?

OF: Excellent. Excellent question. The answer is going to be both, it’s both psychobiological — Whatever flourishing is, it involves positive features of your psycho-biology but it also involves certain social features and it involves culturally specific features.

So next week, there’ll be yet again another annual World Happiness Report that comes out.

Most people, if you ask them what they want out of life they’ll say they want to be happy that’s what Aristotle's word Eudaimonia. He said, Aristotle in fourth century BCE said I go around asking people what they want out of life, and if there's anything they want for its own sake, and the only thing they say is Eudaimonia. Which translates as happy spirit. In philosophy: Flourishing, or fulfillment, or something like that.

Now there are debates then and now about what happiness consists in.

Some people at Aristotle’s time said it's money.

Others said fame and reputation make for happiness..

Others were hedonists and said it was sex drugs and rock n roll.. Aristotle said those definitions are all wrong, What it really consists in is a life of, developing your intellectual capacities your aesthetic capacities and your capacities to be a good human being -- for virtue.

[FX-World Happiness Report]

OF: Interestingly enough during COVID, peoples’ individual rating of their happiness did not go down—that’s kind of interesting. But when you look at the studies that people did of what makes for happiness, it isn’t just sort of a inner feeling state--like happy happy joy joy click your heels.

[FX-Shiny Happy People]

OF: The explanation for why happiness didn’t go down now, is that humans usually when faced with challenges have a sense of meaning and significance and solidarity.

Even in places -- in fact this morning I saw the data from Italy. Even in places like northern Italy where it was terrible Covid, and it still is, by the way, people judge themselves as flourishing more than they usually flourish. Now clearly that isn't to do with narrow physiological states in the brain, although there might be such states in the brain that you could look it, but it has to do with a recommitment that people were making to a social life with a common goal and a common end.

EB: The other thing which we are just starting to touch on is what philosopher David Chalmers named the hard problem. The hard problem of consciousness. Owen Flanagan notes he published Chalmers' article on this in a series he edited. Later on, Owen Flanagan wrote his own book on the subject titled The Really Hard Problem.*

*Flanagan, Owen. The Really Hard Problem: Meaning in a Material World (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2007.)

EB: My understanding is you believe this problem can be solved or gotten to the bottom of.

OF: So. When people say that consciousness is a hard problem, what they mean is it's hard for us to see how the objective physical stuff that makes up brain tissue--even with the electrochemistry involved and the neurobiology involved-- how that yields he subjective technicolor of experience.. Unlike Dave, I'm an optimist that we are solving that problem .. in same way we are solving problem of life. Like, how life evolved. ..etc. (portion missing)

There is lots of sorts of scientific stories about how things emerged that were not there before...What I call the really hard problem, that I claim is an even harder problem, is this.

Assuming that consciousness is hard to figure out, what gives my human life meaning at all? Traditional views about that are that what gives my life meaning is roughly the life to come afterwards. That I'll be able to continue as myself or some version of myself in an afterlife.

math. etc. (portion missing)

Trouble is .. ashes to ashes, dust to dust, stardust to me, back to stardush, that is disenchanting and creates anxiety for lots of people who are antecedently believers in the other story. So what I've argued in my work on the really hard problem is: This is one of the tasks of our age, to come to grips with the view that we're animals and have one life and then we're done. .. and figure out ways to get to the other side, still thinking of human life as a positive, meaningful thing, without those kinds of promises.

music {27:45 - 28:02}

_____

Part 3: Vincent di Fate with Mary Jo Vath.

Mary Jo Vath describes how sci-fi illustration became her pathway into this project.

EB: And finally today we bring this back around to the realm of popular culture, which describes back to us so much of what we think about, worry about and can't really talk over so easily most of the time.

Vincent di Fate: That's .. uh.. Right now everyone on the planet is interested in talking to me.

That's my Twilight Zone esque ringtone.

My name is Vincent di Fate and I've been a science fiction illustrator for 53 years

VdF: The real science of science fiction isn't even quantum physics or the physical sciences. It is really the soft science of psychology, it's really about sociology.

MJV: I found it compelling because I could see it was descriptive of the mass culture view of the brain, brain science and advance in technologies. And I think it probably still is.

So I see it as a repository for some of the best thinking around thje brain, fears around the brain, and also Cold War issues.

MJ asks VdF: If there was a golden age do you divide it into science fiction magazines, then movies in a later golden age?

VdF: There was a great age of ideas in science fiction literature and that really started to take shape during the era of the pulp magazines but there is a golden age we refer to and that’s the 1950s. That’s when the genre--from occasional films that used science as a rationale for why there’s a monster in the story--to a period where science was absolutely indispensable in this storytelling, that would be the 1950s.

The 1950s movies are really preoccupied either directly or metaphorically with loss of identity, which is one of the things we grapple with in the technological age.

If you take a story like the Incredible Shrinking Man, I don't think anyone seriously imagines humans are going to shrink one day but. It’s a metaphor for what is the man of the future going to be like?

[FX-Incredible Shrinking Man. Orson Welles]

OF: And you know Richard Matheson, the author of the original story and screenplay for that movie, was very existential in his beliefs. He thought thought was the important thing. That the body was the illusion, that the consensus realityis the illusion. That what goes on here, that brain in the bottle, on the shelf in the lab, that's what matters. Thought. Our ideas matter.

MJ Yeah, the sci-fi brain is often shown disembodied--sometimes in a jar or a vat. That usually points to something nefarious if you see the disembodied brain in the vat.

It is either about a villain on life support, like in Donovan’s Brain, or in the grade- Z movie, They Saved Hitler’s Brain or it has to do with brain theft, unwilling robotization, loss of individuality.

VdF: Even in our most idealized view of the human brain, it is a rather homely organ and has enormous shock value in its appearance. It's slimy. And if you're gullible enough to believe Donovan's Brain it also pulsates and has a light that goes on and off.

[Fx: Donovan's brain]

VdF: Part of all this landscape of storytelling and fear of the unknown, is the brain, and how the brain works and what the brain means and is the brain the home of the soul, and are they different from one another, and by the way what the hell is this all anyway?

MJV: Yeah, brain being a receiver and this relates to the brain in the vat philosophical problem that goes back to Descartes. Which is: How do I know that an evil genius is not supplying me with all my sensations and experiences? How do I know: I am I?

[Fx: The Matrix]

MJV: So people will recognize a version of this question from the movie The Matrix. Keanu Reeves plays Neo, a character who manages to escape a simulated reality.

VdF: The debate we should be having on the cusp of artificial intelligence is the impact of what AI means. When (Isaac) Asimov wrote about robots-- he invented the robotic laws

{Actually, John W. Campbell invented the robotic laws and gave the idea to Asimov and told him to write a series of stories about inherent violations of the robotic laws. }

But inherent in the robotic laws are safety mechanisms that protect human beings . so as we continue to develop Artificial Intelligence, and machines that give them locomotion we’re going to have to think seriously about building in those safety features.

So how we treat them.

What does destroying a self-aware machine constitute? Is that murder?

Those are moral ramifications we have to really reason out so we have some pre-set method of dealing with them, that's not tainted by emotion or fear or any of the other things human beings are privy to.

MJV: And ethical questions, huge ethical questions, especially in AI and with cyborgs particularly, where you make a being that's neither machine nor human and is accepted nowhere, or doesn't belong anywhere. And this is a huge ethical problem.

VdF: Are we really the individuals we imagine we are? Or are we part of some hive mind which is a much more efficient way to organize culturally?

I would say the new golden age of cience fiction films is still out there. And a new golden age of science fiction literature is still out there waiting to happen.

So the real honest to god golden age of science fiction films lies yet ahead.

{-30-}

Producer and Host: Ellen Berkovitch

Co-Producer and Interviewer this episode: Mary Jo Vath

Guests: Larry Lockridge, Owen Flanagan, Vincent di Fate

VoiceOver Artist: Roberto Sharpe

Post-Production and Theme Music: Dennis Javier Jasso

Creative Commons Samples: Spinning Merkaba, The Stars Look Different under a creative commons license courtesy ccmixter.org

STEAMPlant Team: Ellen Berkovitch, Mary Jo Vath, Iliyan Ivanov, Agnes Mocsy

Funding: STEAMPlant grant from Pratt Institute.